Here’s a report from Charles Stehle on the visit to Carlisle Indian School in October.

Two weeks ago, I took my grandson and son in law to Carlisle where the Pa. Cumberland County Historical Society held a two day symposium called Carlisle Journeys.The subject was “American Indians in Show Business” which explained how. the Carlisle Indian School influenced the entertainment world yesterday and today.

Two weeks ago, I took my grandson and son in law to Carlisle where the Pa. Cumberland County Historical Society held a two day symposium called Carlisle Journeys.The subject was “American Indians in Show Business” which explained how. the Carlisle Indian School influenced the entertainment world yesterday and today.

I found out about this because the Lakota spokesman for the Spotted Tail tribe, Trudell Guerue, who lives in Minneapolis, MN, called me a month ago and told me that the Spotted Tail family in South Dakota would be making a trip from there to Carlisle Pa. to attend the Symposium, mainly to pay homage to Lakota children from the Spotted Tail tribe who were buried there. Unfortunately the tribal elders were not able to make the trip. However they appointed Trudell Guerue, a Lakota family member and Viet Nam army veteran and retired attorney from St. Paul, MN to represent them, and take dirt from the reservation, and water from a stream nearby to be sprinkled on the graves of their ancestral tribal children who were buried in a Carlisle cemetery.

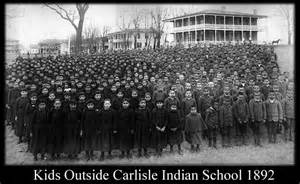

These were Indian children who were taken from their homes in the 1880s on the pretext that they would be educated in the ways of the white man which Spotted Tail and other Sioux leaders thought was a wise thing to do. However, the army captain in charge of this Indian school had orders to force the savage character out of these children and convert them to Christianity. The initial results of this experiment was a disaster, since their hair was cut and they were beaten if they spoke Lakota, Later the children got better treatment, but many of these children died while at school, and then put in unmarked graves.

Many children graduated from this this school and went into movie business, cast in minor Hollywood movies. Some of the speakers at this symposium were descendants of these graduates who to their delight discovered their ancestors had interesting lives in the old western movies. One interesting speaker was a biographer of Jim Thorp the great Indian athlete who was from the Carlisle area. The tone of those stories were light and pleasant, however the opposite point of view came from Trudell and two other Indian speakers who reminded the audience of the sadness of what these Indian children faced, being taken away from their families for years and put in an environment hostile to their culture.

In a northern section of the city of Carlisle,is the Carlisle Army Barracks, where there is a small grave yard 100 ft. long by 30 ft. wide. It is located just inside the barracks where one can see grave stones of unknown Sioux Indians , as well as those of several other tribes, who had died at Carlisle sometime in the late 19th century. In all probability, many of the Sioux graves belonged to the children who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Early Sunday morning, after the symposium was over I, my son in law, grandson, and Trudell, along with a handful of people who had attended the Symposium, all went to the Carlisle barracks grave yard with Trudell’s containers of the dirt, water, and sage that he had brought with him from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota.

To begin the Lakota ceremony I placed the dirt at the base of some twenty Sioux graves, while a friend of Trudell poured the water on the dirt I had spread. When that ended the sage that my grandson held in a skillet was lit and he walked around the people attending this service with smoke wafting from the sage which moved skyward toward the Great Spirit, Wakan Tanka which carried with it the spirit of those attending , and the souls of those Indians whose graves now held the soil and water from their homeland.

After that, Trudell looking toward the sky and moving clockwise, said prayers of thanks, facing North, East, South, and West, Emotionally shaken after the ceremonies were over I and others embraced him.

With that, the ceremonies were over; a fitting end to a wonderful weekend.

Perhaps you’ve heard about the effort to westernize Native Americans that took place during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Indian children were taken (sometimes forcibly) from their families and sent to boarding school to be taught English, Christianity, and European culture so they could assimilate. Probably the most famous of these schools was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania which operated from 1879 until 1918. An estimated 10,000 Indian children attended the school during these years; many from the Lakota tribe. Spotted Tail sent some of his family to Carlisle to study.

Perhaps you’ve heard about the effort to westernize Native Americans that took place during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Indian children were taken (sometimes forcibly) from their families and sent to boarding school to be taught English, Christianity, and European culture so they could assimilate. Probably the most famous of these schools was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania which operated from 1879 until 1918. An estimated 10,000 Indian children attended the school during these years; many from the Lakota tribe. Spotted Tail sent some of his family to Carlisle to study.